Products solve problems for people.

We employ products to do jobs.

Underpinning every Growth Machine is a fundamental understanding of exactly how our product creates value for our customers. Until we understand this, nothing else will make sense to us or our customer.

This article will help you articulate your core value proposition. To do this, we will be using the theories of Christensen, Porter and Foster.

What is a core value proposition?

A core value proposition is an articulate explanation of the underlying problem that your product or service solves for your target market.

Your core value proposition is best defined as ‘the overarching problem your product actually solves.’ It’s the function or feature that makes your company/product unique.

With this said, don’t just jump to the first thing that enters your mind. Think about it more deeply. Ask yourself the following question: ‘when a customer employs my product, what problem are they trying to solve?’

The best value propositions are rarely longer than a line. In fact, the very best might only be two or three words. Here are a few examples:

- “Cheap flights” – Kayak

- “Instant coffee” – Nescafé

- “Healthy burgers” – Grill’d

- “CE/CPD Compliance” – Ausmed

Channel your inner Karl Marx and stay pragmatic. Think about the utilitarian way of describing your company or product. ‘People use our company or product to…’

Your core value proposition (CVP) isn’t designed to be presented to your customers either. Instead, think about them as a simple, verbal articulation for you or your team’s eyes only. Something so simple, that your team could sense-check the work they do against the CVP statement on a daily basis. Much like a null-hypothesis, your team should be able to determine whether or not the core value proposition is being delivered upon.

Case Study: Dollar Shave Club

For example, Dollar Shave Club goes to market with the phrase “A great shave, for a few bucks a month” (nine words). Although this is a very succinct articulation of how they create value, it doesn’t describe the job they actually do or the problem their customers have employed them to solve.

Dollar Shave Club’s job to be done might be described as ‘never running out of sharp blades’ or ‘always having sharp blades handy’ or even more simply put… ‘a cheap, sharp shave’.

Again, core value proposition (CVP) is what you do, not how you do it.

Why does all of this matter? Because if you can’t work out why or what you do for your customers, it’s going to be very hard for your customers to figure it out.

Conveying the right message in your marketing is absolutely critical. The internet is the short attention span theatre. As marketers, we have only a few seconds to capture our target customer’s attention (and just a few more seconds to hold it).

Capturing someone’s attention relies on us being able to quickly and effectively align our product (solution) with their problem.

Life Without Core Value Prop Clarity

Let’s take a moment to imagine marketing without core value proposition clarity.

A marketer’s role is to take a product to market in a way that gets the highest conversion possible. The problem here is that often we don’t actually know what that message is. So, what’s the first thing we do? We hold meetings, draft ideas and stumble through all these conceptual ideas, random notions and biased beliefs about what our product does.

These confabulated ideas are then packaged up into a document, presented and agreed upon in the board room, campaigns are drawn up, user experience and market research is undertaken (often to re-affirm our own biases), design and media agencies are wheeled in and we ‘launch’ this new message or feature to the market.

The numbers look great to start with, as they always do (it’s new), but wain very quickly.

As the numbers deteriorate (purely because the low hanging fruit has been shaken from the tree), most marketers turn to A/B split testing to start identifying, through conversion rate optimization, better ways to optimise this local maximum. Conversion rate optimisation (CRO) is a fantastic process. It involves testing changes to images, ideas, copy, CTAs, offers, asks, layouts against the current version to determine which changes move the needle. (But despite the magic of this methodical approach, taking a pile of garbage and optimising it still leaves you with a pile of garbage.) So, testing begins and the team start optimizising towards the highest converting combination of these features.

Over time, and in pursuit of higher conversion rates, the marketing team begins to present and describe the product in a different light to how it actually works? We call this the local maximum.

The reason why problems like this emerge is because marketers use CRO as a starting point, not the optimisation tool it actually is. This type of siloed approach leads to a product/marketing mismatch.

Ultimately, customers sign up for solution X, while the product team is building solution Y.

Remember, the customer experience erodes when the marketing doesn’t match the product.

The Minds Behind Core Value Proposition

Clayton Christensen – Jobs to be Done

Christensen describes CVP using a concept known as ‘Jobs to be Done’ (JTBD). We’ve already discussed this concept briefly, but let’s explore it a little more deeply.

With JTBD, Christensen poses the following question: ‘what is the underlying job to be done that your product is being employed to do?’

For example, what is the underlying job to be done for a bottle of water? To hydrate? To hold water and make drinking easy? Maybe. Or, could it be portability?

Let’s simplify the question: why would you choose a bottle of water over a glass of water?

It’s light-weight? It’s convenient? How about when you’re heading out for a run, which do you choose? A bottle. Why? Well, are you going to carry a glass whilst you run? No.

The underlying job to be done of a bottle of water is therefore portability.

This means that the people who are in the bottled water business are actually in the portable hydration business. So not only are they competing against other hydration products, but they are competing against other portable water products. Against your own bottle, small bottles, large bottles, water fountains, non-consumption, etc.

“Portability” is a bottle of waters core value proposition.

So if our core value prop is portable water, how can we innovate on that? A clue: it’s not by adding flavour. This is where Michael Porter comes in…

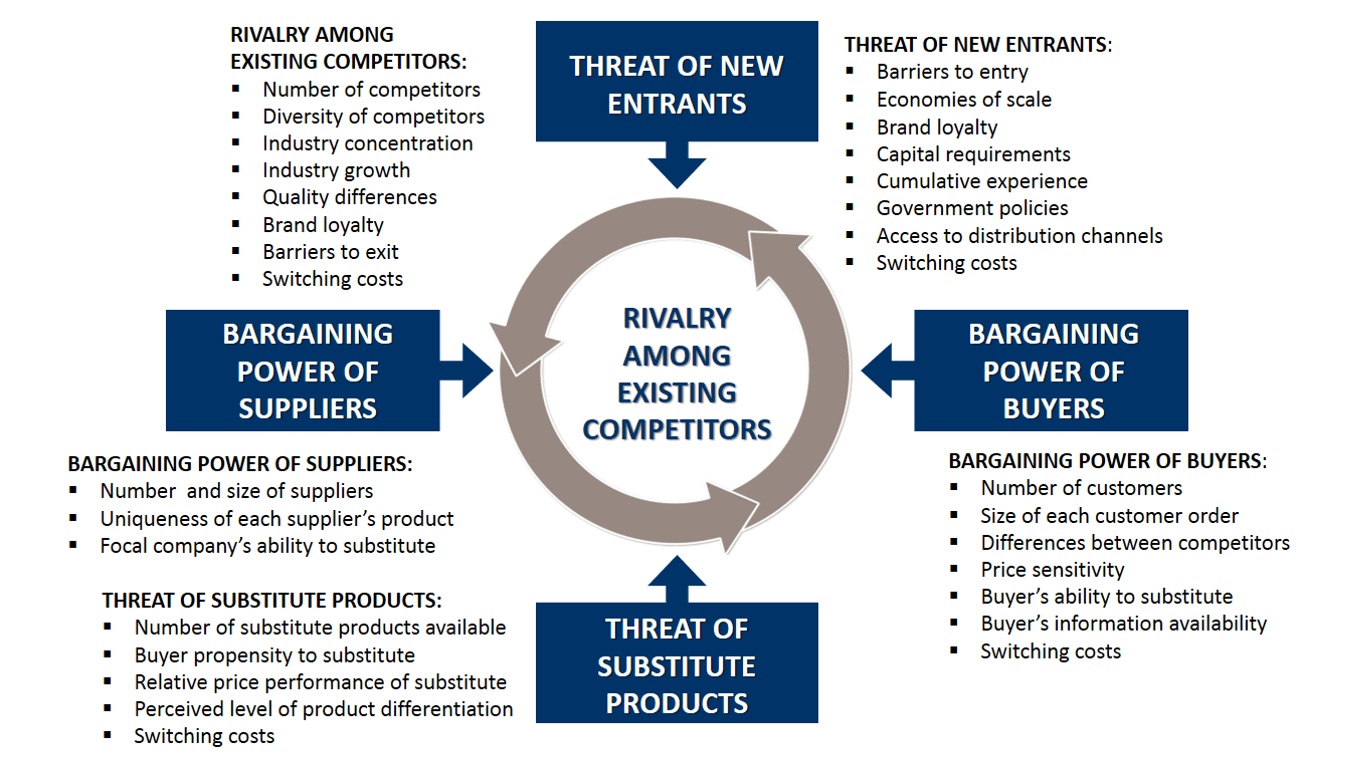

Michael Porter – Porter’s Five Forces

Whereas Christensen can help us work out what the CVP is (and subsequently how new market-entrants can use improved CVPs to disrupt incumbents), Porter helps us understand how the industry might change in its own right. To do this, Porter developed the Five Forces model.

The basis of the five forces is the question of ‘how does an existing player in the market become disrupted’.

There are five ways according to Porter, and consider these not just from a defensive position, but from an offensive position too.

Rivalry amongst existing players – incremental improvements designed to give an incumbent incremental advantage of its competitors.

Threat of new entrants – how undisrupted or stagnant is the industry (construction)? Is it a trending industry (fintech for example)? Are investors looking at this area? What are the setup costs involved in the industry?

Bargaining power of suppliers – how much control do suppliers have over how the industry operates? In the airline industry for example, fuel prices could change any day, causing turbulent (you’re welcome) price wars.

Bargaining power of buyers – how much control do customers have over the product? In the airline industry, not much. But in the recruitment market, probably more.

Threat of substitutes – what other ways could your consumers solve their job to be done? A user’s preference is a strong factor in them preferring a train over a plane (different markets will see this differently), or soda over bottled water. But the job to be done is still the same. Uber is classic example of a new market entrant changing an industry by substitution (both on the driver and rider side).

Porter’s five forces are important in considering the underlying value propositions of the incumbents in an industry, and how you might best address or exploit them. But what happens when we don’t change anything at all?

Richard (Dick) Foster – Incumbents don’t innovate

Dick Foster, the lesser known of the three, explores an industries resistance to change. Specifically how a market’s incumbent strategy defaults to persistence (maintaining the old or failing innovation rather than innovating beyond it or disrupting it).

Foster demonstrates this through a story that dates back to the late 1800s / early 1900s when sailboats ruled the seas. Wooden sailboats were the market incumbent. Then all of a sudden, this new invention called the steamboat started to gather some traction. People were gawking at the idea of lighting a fire on a wooden boat. “Are you mad?” they exclaimed.

In an attempt to prove the viability of such an innovation, the steamboat manufacturers decided to race a steamboat against a sailboat from New York to London. But it took the steamboat three times as long because the sailboat had a really great wind. So the gawking continued.

Curiously enough, what the steamboat companies did next was rather like “growth hacking”, they fixed sails to their steamboats as well. A great interim solution, but something that certainly added to their mocking.

Yet sure enough, over time as the steam-engine technology advanced, the steamboat became faster and faster until one day it eventually beat the sailboat on the New York to London voyage.

Gradually, buyers of sailboats decided steam boats weren’t that bad after all. Why? Because they’re not in the business of buying sailboats, they’re in the business of moving things from A to B as fast as possible. If the sailboat is better today, great. If the steamboat can do that job to be done better tomorrow, even better.

The lesson could end here, but what happened next is certainly worth remembering…

So what did the sailboats do? They persisted with their incumbent technology and began implementing what’s described as a sustaining or efficiency innovation… they added more sails to their boats. It worked. Sailboats were faster again.

Sure enough, a little while later the steamboat was faster again. So, what did the sailboat companies do in retaliation? You guessed it, they added another sail. And on and on it went. Until one day when the sailboat had so many sails on it that it became so unwieldy that it couldn’t be stopped. Flying in from a voyage form New York to London it crashed into the port with such momentum that the entire ship almost ran aground.

This is why a Growth Machine must be built around the underlying job to be done.

Is Core Value Proposition the same as Product Market Fit?

No. These are two different things.

Core value proposition is a simple articulation of the problem you solve only. It’s how your product creates value, but it’s not the product itself.

A product is the combination of a problem and a solution. The solution is what you create and sell, the problem is what your customers have and are prepared to pay to fix.

Once you’ve found alignment with these two things, you now have a product. Product market fit is when you have identified a good enough solution to a common problem that enough people have whereby you could build a company that makes and sells the product. In other words, your product addresses a market that’s large enough to build a business in.

Product market fit might be a familiar concept to you as it thrown around A LOT, and for good reason. Most investors use it to determine whether a business will be successful.

Okay, so what is product market fit then? To fully understand this, we need to look at how problem solution fit and product market fit work together.

The essential foundation for any product or service is that it satisfies a user’s need (a JTBD). Typically, we are well aware of what our problems are as a user (not always though). But that doesn’t mean we are great at understanding how to solve them, and this is where the opportunity lies for entrepreneurs.

If there is a problem and we have (or can develop) a solution to that problem, it’s likely that we have found our problem solution fit.

This might sound obvious, yet there are many examples of people who have had an idea on a whim, spent thousands or millions developing the solution only to find no one has the underlying problem. Their fatal mistake could have been avoided by following these two steps in this precise order.

- Confirm problem solution fit → Develop a minimum viable product (MVP) to ensure your solution actually solves genuine and common problems your target users regularly have.

- Confirm product market fit → Once you’ve got problem solution fit, you then need to work out whether enough people have this problem. If the problem is big enough, there should be a decent sized market for what you’re planning on selling. This is the part investors want to hear.

Once we make it past these two checkpoints, we’re almost ready to start scaling! But before we do, let’s take one last look at Core Value Prop through the eyes of our beloved software engineers.

How Engineers Describe Core Value Prop

Engineers are the best at identifying what a business does? Why, because they’re the ones building it. You’ve probably never noticed it, but almost every market-leading product actually only does one thing. This one thing in marketing speak is the ‘job to be done’, but in software development this is described as the core function. (Engineers use the word “function” to describe the things your product can do.) This core function is designed to allow users to access the product’s core value.

Accessing this core value is typically easy for the user and fast in the best products. It may be coming to the front of your mind now:

“Hey, my favourite app is awesome because it does X!”.

This is why Uber Eats is a different app to Uber for taxis.

Now ask yourself: how fast does your product deliver on its core value proposition? The best products do it immediately.

Case Studies

Let’s take a look at some of the best products and try to articulate their core value proposition and correlate it to the core programmed function.

Google’s core value proposition → A search engine that knows exactly what you mean, and gives you back exactly what you want.

Google’s core function → A search function. (Text input bar and ‘search’ button.)

Google has always solved informational based problems by quickly and accurately finding the best information for people (problem solution fit ✓). Oh, and by the way the whole world wants fast answers (product market fit ✓).

Something particularly interesting about Google is that fact that they found product market fit on day one. Take a historical look at Google’s first search product (below), despite the billions of dollars invested in their software development it still looks the same?

Why? Because once you find the interface that delivers core value prop, you want to avoid deviating from it as much as possible. So, what has Google spent all that money on then (asides from free food and beanbags of course). Well, most of it has gone to making the search function faster, more accurate, more comprehensive etc. Google found product market fit on day one.

Uber

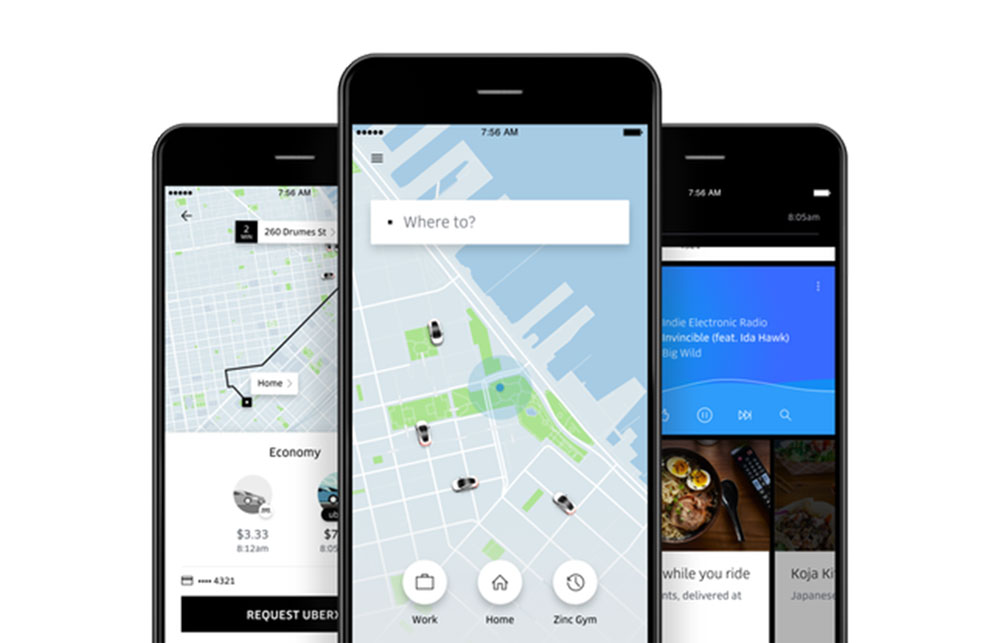

Uber core value proposition → Tap a button, get a ride.

Uber core function → Match a rider with a driver. (Text input bar and ‘request Uber’ button.)

Uber solves a multitude of travel related problems. The primary problem being the lack of quick, accessible and relatively cheap transport options (problem solution fit ✓). This is a mass-market issue, validated by the fact that humans have been travelling between locations since day one.

Just like Google, guess what? Uber’s core function hasn’t deviated a whole lot. Let’s go back in time and look at Uber V1.

The core function again is still the same and like Google, Uber has certainly spent a lot of money improving their product. What have they done? Enhance the core function of matching drivers with riders. The application now sources drivers in a more intelligent manner and supplementary features have been built to enhance this core value prop only.

The most poignant example of this is the sheer fact that Uber Eats is a separate app to Uber. Most companies or marketers wouldn’t think like this. They would make ‘ordering food’ another feature/menu item on the existing Uber app. In doing so they would convolute the interface and increase the user’s cognitive load. This would also break the user’s schema, de-skilling them, and resulting in them regressing in their ability or confidence to use the app. You’ll know this is happening if you hear your customers exclaim “they’re always changing it.”

The core function, that big green button is still essentially the same. A monkey could probably slap the screen a few times with the Uber app open and order a ride. Which is awesome and probably an apt metaphor considering drunk people seem to easily be able to use the app.

So what’s the lesson in all of this?

Test your product with drunk people. Oh, and many of the world’s best products start by focusing on achieving problem solution fit. They then design an interface that delivers upon this core value proposition as fast as possible.